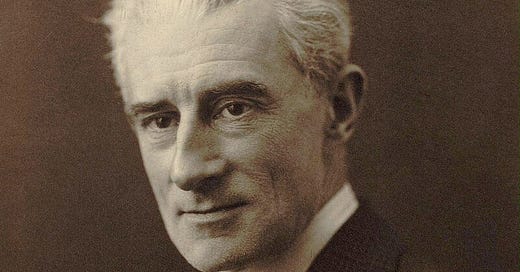

Ravel's Gaspard De La Nuit - I. Ondine (Part 1)

The 3 movements for piano by Maurice Ravel based off of Gaspard of the Night; a collection of poems from Aloysius Bertrand

In their teenage years. Ravel and his close friend Ricardo Viñes, shared an enthusiasm for the stories of Edgar Allan Poe. As Viñes writes in his diary: “August 1892. Wednesday 10, after lunch I went to Ravel’s … Maurice showed me a very gloomy drawing he has done for a descent into Edgar Poe’s Maelstrom. When I was there today, he did another one, also very black, for Poe’s Manuscript Found in a Bottle.” Ravel was clearly drawn to the Gothic imagery of Poe’s tales. Nevertheless, he would never write any music that drew direct inspiration from them.

Around the year 1896, Viñes introduced Ravel to Gaspard de la Nuit, a small volume of prose poems by Aloysius Bertrand, a contemporary of Edgar Allan Poe who displayed a similar predilection for the macabre, the mysterious, and the grotesque. This was how Bertrand’s older brother, Frederic Bertrand, describes him: “Surrendering to childish illusions, he welcomed strange voices coming to him late in the night: the rush of wind in great trees, the cry of a gull, or that of a lost dog echoing in the distance, stirred within him the ivories of an unknown keyboard.” Bertrand’s Gaspard de la Nuit was published posthumously in 1842 and subsequently fell into obscurity. It was through the efforts of Charles Baudelaire that these poems became more widely known. Significantly, Baudelaire was also among the first to translate the works of Edgar Allan Poe into French, providing a source of inspiration for the French Symbolist movement in the final decades of the 19th century. Given this context, it’s evident how Bertrand’s poems were a match made in heaven for a young composer such as Ravel.

In an introductory story, Bertrand relates how he encountered a peculiar old man named Gaspard in a garden in Dijon. Upon recognizing that Bertrand was a poet, Gaspard launched into a lengthy philosophical discussion about the nature of art, of God, and the devil. Then, Gaspard handed Bertrand a manuscript, a collection of poems which was the fruit of Gaspard’s long and laborious study. He told Bertrand to read it and return it the next day. But when the time came to return the manuscript Gaspard could not be found anywhere. As Bertrand discovered, this was because Gaspard was in hell, as “Gaspard de la Nuit” or “Treasurer of the Night” was in fact the devil. So, this was how Bertrand came to be in possession of the collection of poems, which, we’re supposed to believe, was written by the Devil himself. Ravel selected three poems from the collection, I. Ondine, II. Le Gibet, III. Scarbo. And began working on Gaspard de la Nuit in 1908. The compositional process proved to be quite a struggle. As Ravel writes, “Gaspard has been the very devil to finish, which is not surprising since He is the author of the poems.” Always perfectionist and self-critical, Ravel probably thought that only music of devilish complexity would do justice to these poems. Years later, addressing a student who was working on Gaspard de la Nuit, Ravel would make this revealing comment about Bertrand’s work: “It’s marvelous, all the Romanticism of the nineteenth century is found in this little old book.” In this essay we examine the first of these poems and subsequently the piano piece, Ondine.

Ondine is an important figure in European folklore. According to the alchemical writings of the Swiss physician Paraclesus from the Renaissance, there are four elemental beings, corresponding to the four elements: Gnome (earth), Ondine (water), Sylph (air), Salamander (fire). So Ondine is the elemental water spirit. In English, her name is often spelled with a “U” resulting in Undine, which clarifies the derivation from the Latin “unda,” meaning “wave.” The word “undulate” also comes from the same root, reflecting Ondine’s strong aquatic association. Often portrayed as a femme fatale, you can even trace Ondine’s origins to the Sirens in the Odyssey. And whether in the medieval tale of Melusine or Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, the common theme is that the encounter between a mortal man and the female water spirit usually doesn’t lead to a happy ending. Even in modern times, images of the water spirit are ubiquitous; symbols of late-stage capitalism… cough cough Starbucks…

All the poems in Gaspard de la Nuit are headed by epigraphs that are taken from various sources. For Ondine, the epigraph from a poem by Charles Brugnot establishes a veiled, dreamy quality, that ties in relevantly with Ravel’s Ondine.

“. . . . . . . . . I thought I heard

a vague harmony enchanting my slumber,

and near me spreads a murmur like

the interrupted songs of a sad and tender voice.”

Notably we can pick at both “vague harmony” and “sad and tender voice” being quite natural descriptors for Ravel’s Ondine. It’s interesting to note that the encounter between Ondine and the mortal man is not direct and immediate. There seems to be a window between them. So, we can imagine that she’s outside in her beguiling supernatural world, while he’s inside, in some confined space where human reason and logic prevail. Visually, the asterisk in the poem itself makes this separation quite clear. Above the asterisk are the three verses that make up Ondine’s song. If you go and read it, her language is evocative and spatially oriented, painting a fantastic and alluring world that seems to almost exist untarnished by the flow of time. In contrast, below the asterisk are the verses from the man’s perspective, where the tone is more matter-of-fact, emphasizing sequential progression and dispassionate cause and effect. In short, she’s descriptive and he’s dismissive. This is perhaps the most striking aspect of the poem. Ondine’s charms prove so readily resistible, which seems to subvert the typical portal of the water spirit as a dangerous seductress in the literary tradition that Bertrand would have been familiar with. Bertrand’s Ondine seems to be more like the Little Mermaid, perhaps somewhat naive or even puerile, but essentially benign. However, Ondine’s reaction to the man’s rejection raises some doubts about this interpretation. After shedding a few tears, she actually bursts out laughing.

“And when I replied that I was in love with a mortal woman, sulky and vexed, she shed a few tears, let out a peal of laughter, and vanished in a sudden shower which streamed in pale rivulets down my blue window panes.”

What are we to make of this? Is there something sinister about it, as in “You’ll pay for this… I’ll have the last laugh?” Or is it more like the sort of laughter that’s been astutely described in the Book of Proverbs, laughter that actually conceals sorrow?

“Even in laughter the heart is sorrowful; and the end of that mirth is heaviness.”

Personally, I’m more inclined towards this latter interpretation, and I think Ravel’s setting is exquisitely sensitive to the implied emotional depth beneath the flowing eloquence and apparent restraint. As the French composer Roland-Manuel insightfully remarks in his biography of Ravel:

“One must not expect from Ravel works in which feeling is continually exaggerated by the violence of its expression. One must not ask Ravel to stir the dark waters of desire or willingly to reveal the gulfs of despair. If the lake which envelops the wondrous ‘Ondine’ is deep, we gauge the depth by its limpidity. In a word, Ravel’s magic – inasmuch as it exists – is still white magic.”

Now that we have some background information and context regarding both the inspiration for Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit and the subsequent analysis of the first poem that evokes the beautiful painting that the first movement of the piece conveys, in my next post we will delve deep into the musical composition and analyze the harmonies and melodies that portrays the elusive water spirit Ondine.